|

|

|

|

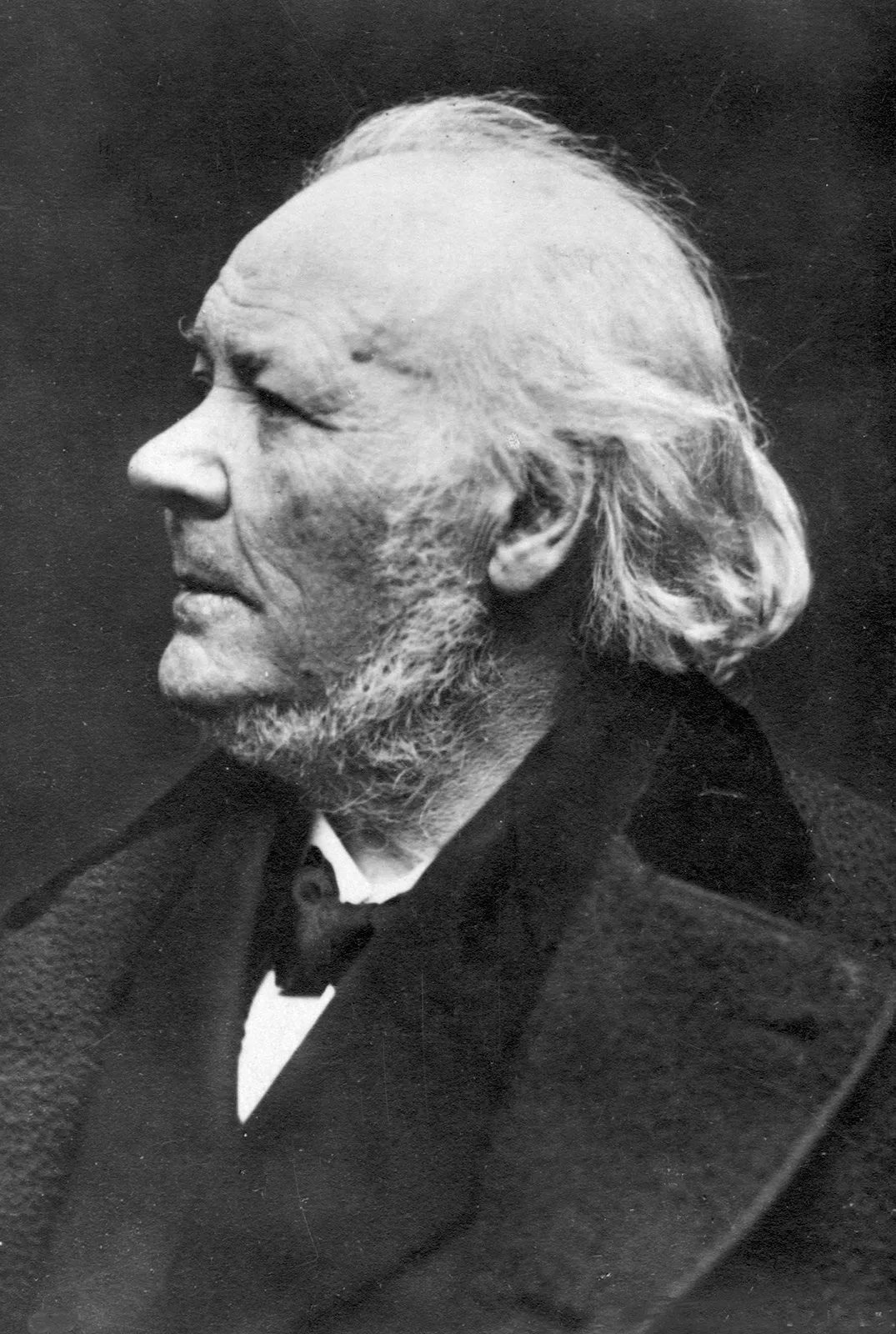

Honoré DaumierPainter, Sculptor, Printmaker

Honoré-Victorin Daumier (1808-1879) was a French activist and humorist whose many works offer commentary on the social and political life in France, from the Revolution of 1830 to the fall of the Second French Empire in 1870. He was a republican democrat (working class liberal), who satirized and lampooned the monarchy, aristocracy, clergy, politicians, the judiciary, lawyers, police, detectives, the wealthy, the military, the bourgeoisie, as well as his countrymen and human nature in general.

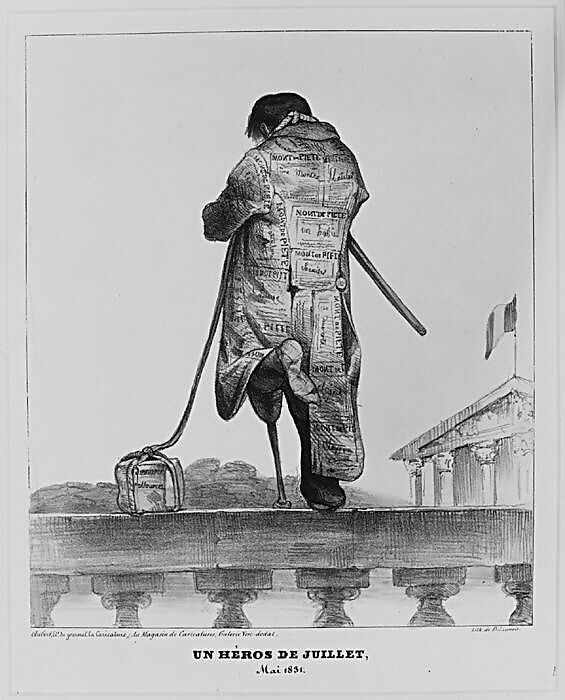

Daumier remained defiant in prison and wrote a number of letters indicating that he was producing lots of drawings "just to annoy the government." He created another masterwork called Un Héros de Juillet, Mai 1836 ("A Hero of July, May 1831"), published in December of 1832 in La Caricature. In the print, a veteran wears a coat made out of pawn receipts and stands on a bridge facing France's Chamber of Deputies. With one foot disabled from battle, his usless walking stick points towards the chamber, while he has tied a paving stone to his neck with a rope, preparing to jump. After his release from prison on February 14, 1833, Daumier moved out of his parents' home into an artist phalanstery on Rue Saint Denis. He resumed work at La Caricature and continued to publish controversial lithographs like Rue Trensnonain, Freedom of the Press, and Past, Present, Future. In 1834 La Caricature finally ceased publication after relentless prosecutions and fines from the monarchy. However, Daumier continued to work at a similar journal called Le Charivari, anyway, so it had little effect on his popularity.

In response to Daumier's lithographs (and an assassination attempt or two), France instituted extremely oppressive censorship laws in 1835. This effectively made political caricatures illegal. Daumier, with some relief, shifted the focus of his caricature from politics to more commentaries on general French culture. Daumier began painting in the mid 1830's and by the end of the decade was very dedicated to producing more oils and watercolors. He had more interest in painting than in caricature and lithography, but he found it necessary to keep producing cartoons in order to have income.

Although Daumier had been painting for a number of years, it was in the late 1840s that he became increasingly dedicated to that particular medium. By the mid to late 1850s Daumier had reached new levels of artistic maturity and increasingly wished to devote himself to painting. After 30 years of steadfast production, he was growing tired and weary of the grind of producing up to eight cartoons a week, yet he was dependent on the income. His caricatures were aalso declining in popularity with the public, and in 1860 Le Charivari actually dropped him from their staff and ceased to publish his cartoons! While the next few years were a time of financial hardship and struggle, they were also years with free time to devote to painting, and a time of great productivity and artistic growth. Daumier's paintings are now well-regarded, but at the time of their creation they were largely unappreciated. His paintings did not start increasing in value until after his death. Daumier painted about 500 paintings in oil and watercolor on a variety of subjects including many portraying Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. He started experiencing failing eyesight around 1865 or 1866 which progressed with time, although he was still producing drawings and poster designs as late as 1872. He continued to exhibit at the Paris Salons for several years, although the canvases he submitted were often over ten years old. However it was at this point in time that the government of France actually began to appreciate one of the country's greatest artists. The Second French Empire intended to award Daumier the Legion of Honor; however, he discreetly declined, feeling it was inconsistent with his political ideals and oeuvre. The French Third Republic again offered Daumier the Legion of Honor and again he declined, although he was later granted a pension of 200 francs a month (2,400 annually) in 1877, which was increased to 400 a month (4,800 annually) in 1878. A circle of his friends and admirers arranged a large exhibition of his paintings at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris.This was the first time the full scope and range of Daumier's work was exhibited, and it was very well received by both the public and critics, and became a decisive turning point in the perception of Daumier as an important painter. He died several months later, in February of 1879.  Go back to The Pantheon |