|

Broadcast:

1954 |

|

The show was forgotten about after its initial showing until most of it was located in the 1980s by film historian Jim Schoenberger, with the ending (including credits) found afterwards. The rights to the programme were acquired by MGM at the same time as the rights for the 1967 film version of Casino Royale, clearing the legal pathway and enabling them to make the 2006 film of the same name. The first public screening of the tele-movie in a theater was held in July 1981 not long after it was re-discovered by Jim Shoenberger. It played at a Los Angeles James Bond Weekend where the telemovie's James Bond star Barry Nelson was in attendance.

James Bond was Americanized into "Card Sense Jimmy Bond," a rough American gambler.

Barry Nelson: "A modest effort for what it was. We didn't have all the stuff they have in the Bond pictures. This show was done live at CBS Television City on a budget of $25,000, while the Bonds today (1983) cost $25 million or more. When Connery looks over his shoulder and sees he's being followed, he can just adjust his ring and zzzzzappp! The bad guys are wiped out and melted. I couldn't get a ring like that."

In an interview with Starlog Magazine in October 1983, Barry Nelson said: "So they went through and cut three words here, a line there, a half-a-word here, and their script ended up looking like a bad case of tic-tac-toe. I tell you it was so frightening that when I entered my only thought was, 'Oh, God, if I can only get out of this mother!'. I was very dissatisfied with the part, I thought they wrote it poorly. No charm or character or anything." Peter Lorre played arch-villain Le Chiffre and acted opposite a worried Nelson. Due to the last minute script-changes, apparently Lorre said to the panic-stricken Nelson, "Straighten up, Barry, so I can kill you!".

There were a few live TV bloopers. A gunshot sounded accidentally at one point, names are forgotten or mispronounced, and at one point, when Valerie's hands are bound in a close-up - it is obvious that they were never actually tied.

|  |

|

After Le Chiffre "died," actor Peter Lorre stood back up and headed offscreen to his dressing room. As this was a live broadcast, we can assume this was pretty confusing for the viewers.

Clare Blanshard wrote Fleming a critique of the show and "tore it to shreds." Fleming told her that he laughed until tears were running down his cheeks.

Fleming grew more and more discouraged. Then he met a man named Kevin McClory, who promised to change Fleming's life (and boy, did he).

Casino Royale is a 1954 television adaptation of the novel of the same name by Ian Fleming. The show is the first screen adaptation of a James Bond novel and stars Barry Nelson and Peter Lorre. Though this marks the first onscreen appearance of the character of James Bond, Nelson's character is played as an American agent with "Combined Intelligence" and is referred to as "Jimmy" by several characters.

The show was forgotten about after its initial showing until most of it was located in the 1980s by film historian Jim Schoenberger, with the ending (including credits) found afterwards. The rights to the programme were acquired by MGM at the same time as the rights for the 1967 film version of Casino Royale, clearing the legal pathway and enabling them to make the 2006 film of the same name.

[edit] PlotAct I "Combined Intelligence" agent James Bond comes under fire from an assassin: he manages to dodge the bullets and enters Casino Royale. There he meets his British contact, Clarence Leiter, who remembers "Card Sense Jimmy Bond" from when he played the Maharajah of Deauville. While Bond explains the rules of baccarat, Leiter explains Bond's mission: to defeat Le Chiffre at baccarat and force his Soviet spymasters to "retire" him. Bond then encounters a former lover, Valerie Mathis who is Le Chiffre's current girlfriend; he also meets Le Chiffre himself. Act II Bond beats Le Chiffre at baccarat but, when he returns to his hotel room, is confronted by Le Chiffre and his bodyguards, along with Mathis, who Le Chiffre has discovered is an agent of the Deuxime, France's external military intelligence agency at the time. Act III Le Chiffre tortures Bond in order to find out where Bond has hidden the cheque for his winnings, but Bond does not reveal where it is. After a fight between Bond and Le Chiffre's guards, Bond shoots and wounds Le Chiffre, saving Valerie in the process. Exhausted, Bond sits in a chair opposite Le Chiffre to talk. Mathis gets in between them and Le Chiffre grabs her from behind, threatening her with a concealed razor blade. As Le Chiffre moves towards the door with Mathis as a shield, she struggles, breaking free slightly and Bond is able to shoot Le Chiffre. [edit] Cast

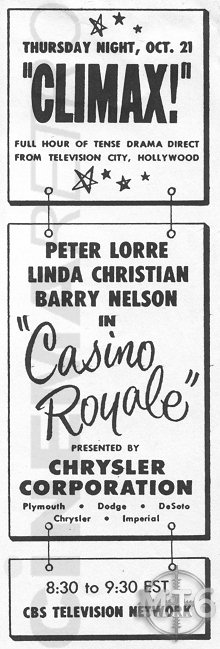

Production In 1954 CBS paid Ian Fleming $1,000[2] ($8,654 in 2012 dollars[3]) to adapt his first novel, Casino Royale, into a one-hour television adventure[4] as part of their dramatic anthology series Climax Mystery Theater, which ran between October 1954 and June 1958.[5] It was adapted for the screen by Anthony Ellis and Charles Bennett; Bennett was best known for his collaborations with Alfred Hitchcock, including The 39 Steps and Sabotage.[6] Due to the restriction of a one hour play, the adapted version lost many of the details found in the book, although it retained its violence, particularly in Act III.[6] The hour-long Casino Royale episode aired on 21 October 1954 as a live production and starred Barry Nelson as secret agent James Bond, with Peter Lorre in the role of Le Chiffre[7] and was hosted by William Lundigan.[8] The Bond character from Casino Royale was re-cast as an American agent, described as working for "Combined Intelligence", supported by the British agent, Clarence Leiter; "thus was the Anglo-American relationship depicted in the book reversed for American consumption".[9] Clarence Leiter was an agent for Station S, while being a combination of Felix Leiter and Ren Mathis. The name "Mathis", and his association with the Deuxime Bureau, was given to the leading lady, who is named Valrie Mathis, instead of Vesper Lynd.[10] Reports that towards the end of the broadcast "the coast-to-coast audience saw Peter Lorre, the actor playing Le Chiffre, get up off the floor after his 'death' and begin to walk to his dressing room"[11], do not appear to be accurate.[12] [edit] Legacy

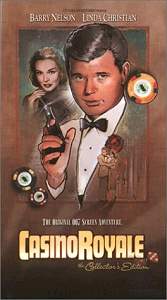

This was the first screen adaptation of a James Bond novel and was made before the formation of Eon Productions. When MGM eventually obtained the rights to the 1967 film version of Casino Royale, it also received the rights to this television episode.[15] The Casino Royale episode was lost for decades after its 1954 broadcast until a kinescope of it was located by film historian Jim Schoenberger in 1981.[16][17] It also aired on TBS as part of a Bond film marathon. However, the VHS release and TBS presentation did not include the full finale of the adaptation, which was at that point still lost. Eventually, the missing footage (minus the last few seconds of the credits) was found and included on a Spy Guise & Cara Entertainment VHS release. MGM subsequently included the truncated version on its DVD of the 1967 Casino Royale.[1] David Cornelius of Efilmcritic.com described it as an "anthology of suspense and mystery yarns performed live in the tradition of television's golden age."[6] He remarked that "the first act freely gives in to spy pulp clich" and noted that he believed Nelson was miscast and "trips over his lines and lacks the elegance needed for the role." He described Lorre as "the real main attraction here, the veteran villain working at full weasel mode; a grotesque weasel whose very presence makes you uncomfortable."[6] Peter Debruge of Variety also praised Lorre, considering him the source of "whatever charm this slipshod antecedent to the Bond oeuvre has to offer", and complaining that "the whole thing seems to have been done of the cheap". Debruge still noted that while the special had very few elements in common with the Eon series, Nelson's portrayal of "Bond suggests a realistically human vulnerability that wouldn't resurface until Eon finally remade Casino Royale more than half a century later."[18] In this tele-movie, Zoltan's gun passed for a cane. James Bond eventually gives Clarence Leiter the cane-gun as a present for Scotland yard's Black Museum. This type of gadget weapon was actually the first ever gadget seen in a James Bond movie. This type of gadget weapon would be repeated in The World Is Not Enough. In this later movie, Zukovsky's (Robbie Coltrane) walking stick also doubled as a gun. [edit] References

[edit] Bibliography

[edit] External links

| |||

The production went mostly unnoticed upon release.

The production went mostly unnoticed upon release.